Part V: The Union

Chapter I: The Executive

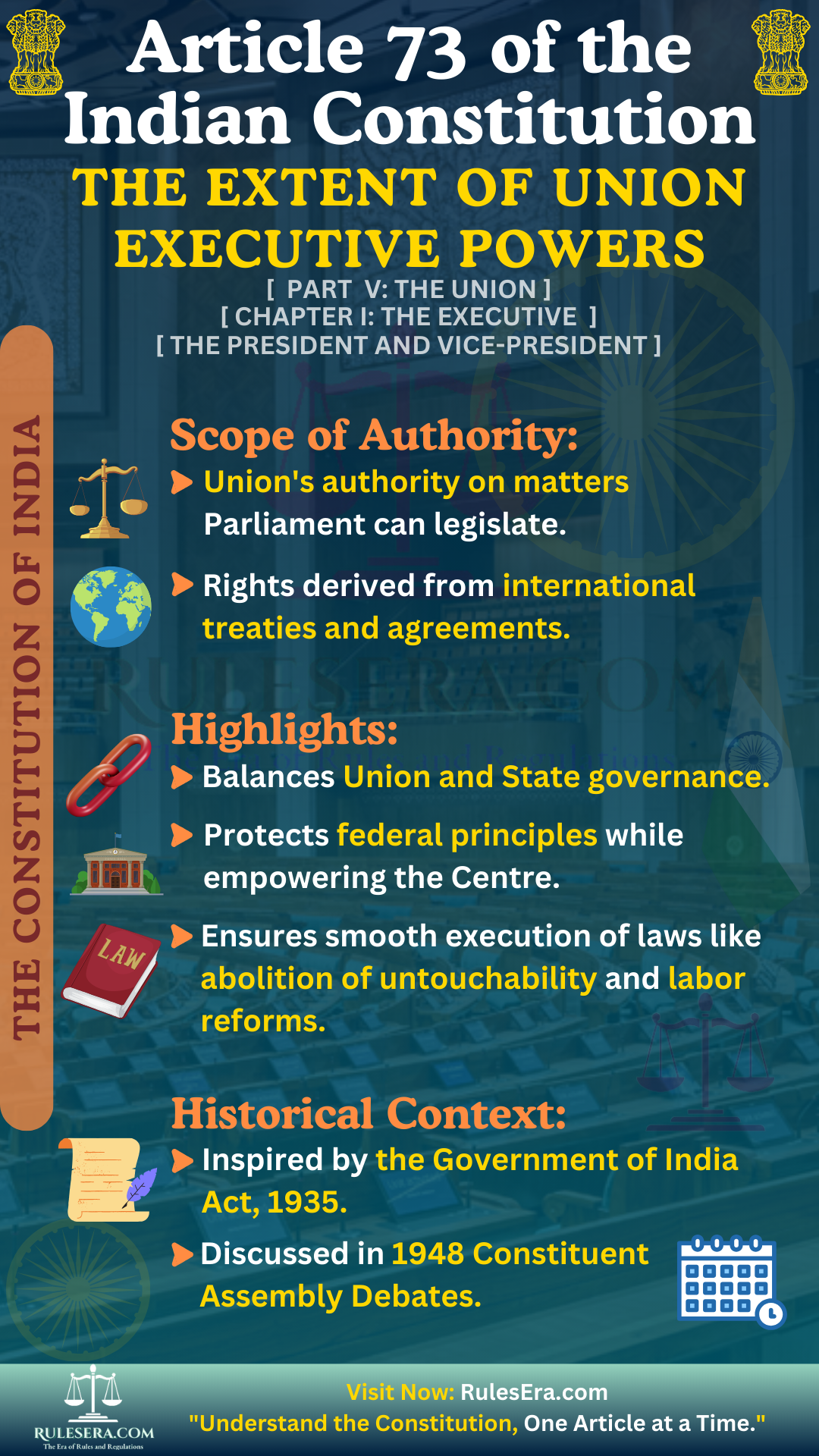

Article 73: Extent of Executive Power of the Union

--- Original Article ---

(1) Subject to the provisions of this Constitution, the executive power of the Union shall extend—

- To the matters with respect to which Parliament has power to make laws; and

- To the exercise of such rights, authority, and jurisdiction as are exercisable by the Government of India by virtue of any treaty or agreement:

Provided that the executive power referred to in sub-clause (a) shall not, save as expressly provided in this Constitution or in any law made by Parliament, extend in any State to matters with respect to which the Legislature of the State has also power to make laws.

(2) Until otherwise provided by Parliament, a State and any officer or authority of a State may, notwithstanding anything in this article, continue to exercise in matters with respect to which Parliament has power to make laws for that State such executive power or functions as the State or officer or authority thereof could exercise immediately before the commencement of this Constitution.

Explanations

Article 73 defines the scope of executive authority vested in the Union Government. This provision ensures that the executive branch of the Union operates within the limits of the Constitution and is empowered to implement laws and treaties effectively while respecting the federal balance with the States.

Clause Headings and Explanations:

1. Clause 1: The Union's Executive Powers

Article 73(1) outlines the Union's executive power to include all matters on which Parliament has the power to legislate. These matters are typically listed under the Union List (List I) in the Seventh Schedule, but may also include areas under the Concurrent List (List III). Furthermore, it includes any executive power related to treaties, agreements, and other international obligations undertaken by the Government of India.

Historical Context: The framers borrowed this provision from the Government of India Act, 1935, which sought to balance executive powers between provincial and federal governments.

Real-Life Application:

An example of this balance can be observed in sectors such as agriculture or education, where both Union and State governments can legislate. The Union Government cannot impose executive decisions without either parliamentary or constitutional backing.

2. Clause 2: Transitional Continuity for States

Article 73(2) acts as a transitional safeguard, allowing States and their officers to continue performing executive functions in areas where Parliament has legislative power until Parliament chooses to legislate otherwise. This clause ensured continuity during the early years of independent India and still holds significance.

Amendments

Although Article 73 has not undergone significant amendments, its implications have evolved through judicial interpretation. The courts have clarified that the Union's executive powers must respect the federal nature of the Constitution, reinforcing the autonomy of the States.

Historical Significance:

Article 73 was designed to avoid the centralization of executive power while allowing the Union Government to fulfill its national and international obligations.

References

- Government of India Act, 1935

- Constituent Assembly Debates, Volume IX

- Judicial interpretations regarding Union and State relations under Article 73

Legislative History

Originally discussed as Draft Article 60, Article 73 was debated on December 29 and 30, 1948, and later incorporated into the final text of the Constitution.

Debates and Deliberations:

Several members debated the proviso to clause (1) regarding its impact on provincial autonomy. Notably, Dr. B. R. Ambedkar argued in favor of the proviso, emphasizing its importance in ensuring proper implementation of laws such as those against untouchability, child marriage, and labor regulations.

K.T.M. Ahmad Ibrahim Sahib Bahadur proposed the deletion of the proviso, arguing that it undermined provincial autonomy by enabling the Union to encroach upon matters on the Concurrent List, thus potentially reducing States to mere administrative divisions under the central government.

Pandit Hirday Nath Kunzru supported this view, advocating for a limitation on central authority over the Concurrent List. He proposed amendments to prevent the Union's executive authority from interfering with subjects within the Concurrent List, preserving State autonomy.

Conversely, Shri T. T. Krishnamachari opposed these amendments, highlighting the need to maintain the balance of power established under the Government of India Act, 1935. He argued that the proviso ensured a clear separation of powers between the Centre and the States, preventing conflicts between their executive authorities.

Dr. Ambedkar also disagreed with the proposed amendments, explaining that the proviso allowed States to generally execute laws within the Concurrent List, with Parliament retaining authority for exceptions. He highlighted specific laws against untouchability and child marriage as examples where Union oversight might be necessary. By ensuring the central implementation of these laws, the Union could relieve States of associated financial and administrative burdens.

Ultimately, the House supported the proviso as it aligned with federal principles, while also addressing practical governance challenges. This balanced approach allowed for the concurrent operation of executive power by the Union and the States under specified circumstances.